Sir Mo Farah is one of the Olympic greats and will go down in British sporting history.

The four-time champion has called it quits after his final race in the Great North Run.

The sight of Farah failing to reach the Tokyo Olympics during a last-ditch attempt in Manchester in June 2021 will not be his enduring image but it will be one when it was clear his time was up.

His dominance was over, the final push was not there and his legs no longer had it in them.

Before then, on the track at least, he had been all conquering and gave British sports fans some of the most memorable moments of the last decade.

None more so than at London 2012 when, already a 5,000m world champion – having failed to make the same final at the 2008 Beijing Olympics – Farah helped create the biggest day in British Olympic history.

Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford added three gold medals in 48 minutes at the Olympic Stadium, after wins in the men’s coxless four, women’s lightweight double sculls and women’s team pursuit earlier in the day.

He stormed to 10,000m gold after Ennis-Hill had won the heptathlon and Rutherford claimed the long jump title.

Seven days later he won the 5,000m to write his name further into British Olympic folklore.

It allowed Farah to become a personality and transcended athletics and the ‘Mobot’ became a symbol of his success.

He adopted it after it was suggested by presenter Clare Balding and then named by James Corden on TV show A League of Their Own just two months before the London Games.

A robot was even named “Mobot” at a Plymouth University research exhibition.

A year after London he became a double world and Olympic champion after victory in the 10,000m and 5,000m at the World Championships in Moscow, the first British athlete to win two individual gold medals at the Worlds.

In 2014 he stepped up to the marathon for the first time, coming eighth in London but continued to shine on the track, defending his world titles in 2015.

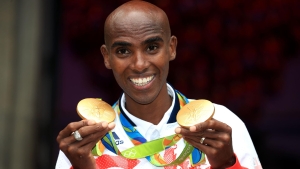

All roads then led to Rio with Farah completing a historic double double by defending his London titles – despite falling in the 10,000m.

“After the 10k my legs were a bit tired, and I don’t know how I recovered. I had to take an ice bath and stay in my room, there were people bringing me food in my room and I was just resting up,” he said.

“I can’t believe I did it. I did it! It’s every athlete’s dream, as I said… I can’t believe it, it hasn’t sunk in yet.”

Back in the Olympic Stadium in 2017 he won another 10,000m world title and came second in the 5,000m in London before announcing his retirement from the track to focus on the marathon.

Yet, aside from a victory in the Chicago race in 2018, he failed to convince.

At the start of his marathon career he also split from controversial Alberto Salazar amid a US anti-doping investigation into the coach.

“I’m not leaving the Nike Oregon Project and Alberto Salazar because of the doping allegations,” Farah said at the time. “This situation has been going on for over two years. If I was going to leave because of that I would have done.

“As I’ve always said, I’m a firm believer in clean sport and I strongly believe that anyone who breaks the rules should be punished. If Alberto had crossed the line, I would be out the door but Usada has not charged him with anything. If I had ever had any reason to doubt Alberto, I would not have stood by him all this time.”

A return to the track to defend his 10,000m title was announced in 2019 and, while the 12-month coronavirus delay to the Tokyo Games gave him more time, it also left him a year older.

At the official trials in Birmingham, Farah failed to hit the qualification mark, finishing 22 seconds adrift, and a hastily arranged race at the Manchester Regional Arena was his final chance.

As the stadium got quieter – with the PA slowly stopping announcing his lap times – it quickly became apparent Farah would not achieve his goal and in the immediate aftermath he hinted retirement was on his mind.

Now, he has officially hung up his spikes but will go down in athletics as an Olympic great.