Iliman Ndiaye feels privileged to be part of the final Everton squad to play at Goodison Park, as the Toffees prepare to resume their Premier League campaign at home to Brentford.

Everton will leave Goodison for their new 52,000-seater stadium at Bramley-Moore Dock at the end of the 2024-25 season.

A run of one defeat in seven matches (two wins, four draws) has boosted the Toffees' hopes of surviving the current campaign in the top flight, and Ndiaye – a pre-season arrival from Marseille – says being part of club history was a key attraction when he joined.

"Obviously, I wanted to be part of that history of playing in the last-ever season at Goodison Park," Ndiaye told the club's website.

"So many things have happened here, it's full of history and we are the last players to represent this club here, so it's important we give everything we have.

"Then, the new stadium that is coming, I think that excites everyone. It's seriously impressive.

"The players who have been here for a long time and the players who have just arrived, I know we are all ready to give more than 100% to have the best season possible and go into the new stadium in a good place."

Brentford are six points clear of Everton in 11th, just three points adrift of Manchester City in third, though all their 16 points have been won on home turf.

Sepp van den Berg has played in nine of their 11 Premier League games this term after arriving from Liverpool, and the defender has heaped praise upon Thomas Frank for making him feel welcome.

"For me, Brentford was one of the first clubs interested and, as well as getting the chance to play in the Premier League and live in London, it was speaking with Thomas Frank," he said.

"The first meeting we had, he was asking me some straight questions: 'Why do you want to play for Brentford? Why do we need you at Brentford?' It was so direct, it was like a proper job interview!

"Of course, the football part has to be right as well – and it was. But Thomas just made me feel like I was really wanted here."

PLAYERS TO WATCH

Everton – Jarrad Branthwaite

Since the start of last season, Everton have a win percentage of 35% and have earned 1.3 points per game in the Premier League when Branthwaite starts, compared to a 17% win percentage and 0.8 points-per-game without him in their starting XI.

Indeed, the Toffees have lost just one of the last eight league games in which he has started (five wins, two draws). The England international made his first start since August last time out in their goalless at West Ham, which was a massive boost for Dyche.

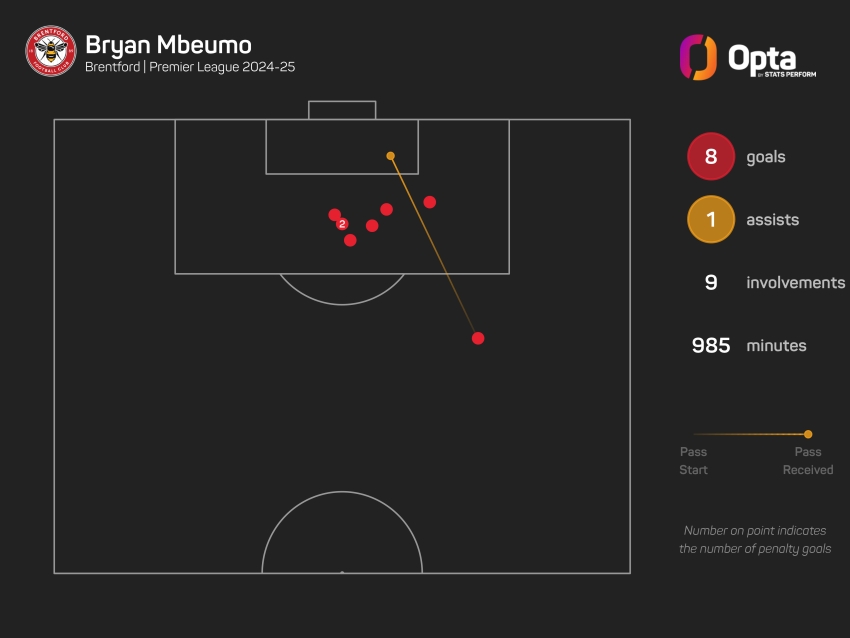

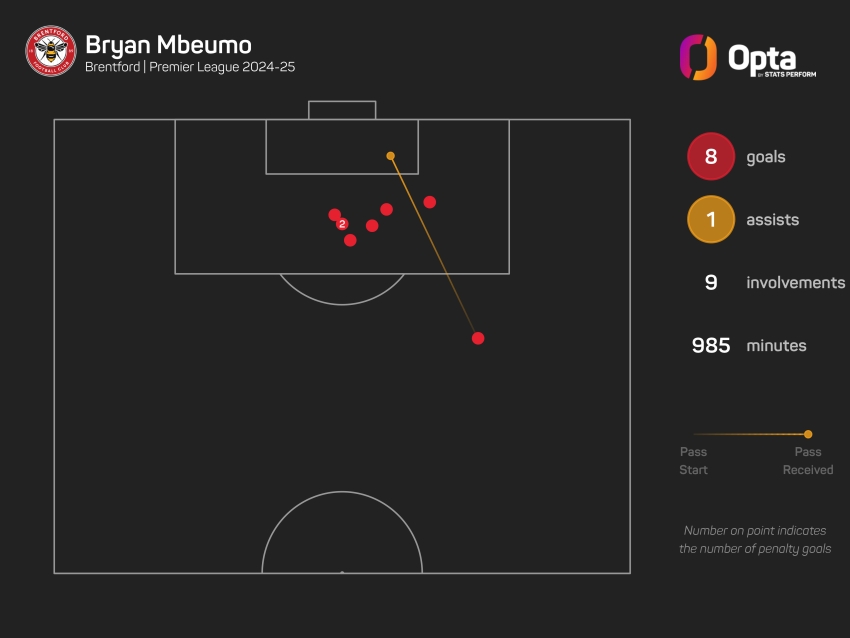

Brentford – Bryan Mbeumo

Only Mohamed Salah (14), Erling Haaland (12), Cole Palmer (12) and Bukayo Saka (10) have been directly involved in more Premier League goals this season than Mbeumo (nine – eight goals, one assist).

He has, though, played more minutes without a goal involvement in the competition against Everton than any other side (528 – 13 shots, five chances created). He will be determined to set that record straight at Goodison Park.

MATCH PREDICTION – EVERTON WIN

This match should offer an interesting clash of styles. Only Crystal Palace (0.089) average a lower xG per shot figure than Everton (0.093) in the Premier League this season, while Brentford are the side with the highest xG per shot in 2024-25 (0.149).

The Bees have seen 44 goals scored across their 11 Premier League games so far this season (22 for, 22 against), the most of any side.

Indeed, only Newcastle United in 1999-00 and Arsenal in 2011-12 have both scored and conceded 20+ goals in fewer games from the start of a campaign in the competition (10).

Brentford have, however, lost all five of their Premier League away games this season; only in 1924-25 and 1961-62 (both nine) have they ever lost each of their opening six or more away matches of a league campaign.

Everton have lost only two of their last 10 Premier League games at Goodison Park (six wins, two draws), while they also have three straight wins against Brentford in the competition, after failing to win any of their first three against them (one draw, two defeats).

OPTA WIN PROBABILITY

Everton – 40.5%

Brentford – 32.5%

Draw – 26.9%