Roberto Mancini has overseen arguably one of the all-time great transformations in international football, not only turning Italy into a team that has a clear and fresh identity, but also a side that is successful.

When they lost 1-0 to Portugal on September 10, 2018 in the Nations League, who'd have thought that by the next time they suffered defeat they'd have won the European Championship? The fact that's the case despite Euro 2020 being delayed for 12 months is all the more impressive.

While the Azzurri required a penalty shoot-out against England in Sunday's final at Wembley, it's fair to say Italy were worthy victors in the end, with their hosts' caution only taking them so far.

In fact, England's pragmatism was arguably akin to the philosophy historically associated with Italy, but under Mancini they've truly embraced a tactical fluidity that has seemingly altered the perception many have of them.

Press smart, work smart

Intense off-the-ball work and a high press have almost become mainstream in modern football. While they aren't necessarily prevalent aspects of every team, not even every great team, many of the world's finest coaches try to implement them to a certain degree.

At Euro 2020, it's been a core strength of Italy – but it's not just a case of chasing down opponents like headless chickens. They've proven themselves to be smart.

The average amount of passes Italy allow their opponents to have in their own defensive third before initiating a defensive action is 13 (PPDA). Seven teams at the tournament pressed with greater intensity, but none were as effective as Italy.

Their 56 high turnovers were matched by Denmark but Italy boasted a tournament-high 13 that led to a shot, while three resulted in a goal – that too was bettered by no other team.

It suggests that, while other sides such as Spain (8.1 PPDA) pressed higher, Italy were better at picking their moments and knowing when to up the intensity.

Italy still managed to remain well balanced, too. Their average starting position of 42.9 metres from their own goal was deeper than six other teams, an important factor considering Giorgio Chiellini and Leonardo Bonucci aren't the quickest.

Yet they still pressed to greater effect that any of the others.

Establishing control

If there was one area of the pitch that you might point out as most crucial in Italy's Euro 2020 success (if we ignore Gianluigi Donnarumma's shoot-out saves), it would be their midfield.

Nicolo Barella, Marco Verratti and Jorginho were largely excellent as a trio, though the latter pair have attracted most of the acclaim.

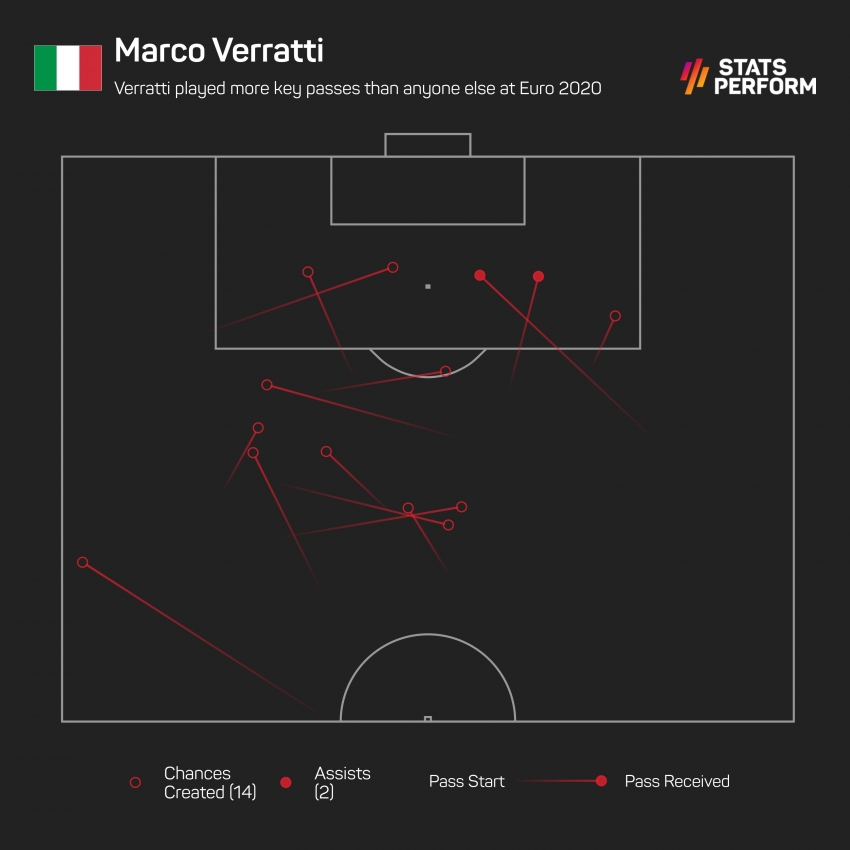

In Verratti, Mancini seems to have a player who truly embodies their style of play – an excellent creator, he also does more than his fair share off the ball as one of the most complete central midfielders in the game today. He puts the fun in functional.

Verratti played the most key passes (14) of anyone at the tournament and ranked fourth for successful passes (87.1) and fifth for tackle attempts (4.0) per 90 minutes (at least 90 mins played).

The Paris Saint-Germain star also provided drive from the centre, with his 23 ball carries per 90 minutes bettered by just five midfielders, though only Pedri moved the ball between five and 10 metres upfield more often than Verratti (47), highlighting his progressive mentality.

Yet he didn't do it all on his own – after all, Verratti missed the first two games through injury. No, Jorginho had a similarly important function as the chief deep-lying playmaker, playing 484 successful passes, trailing only Aymeric Laporte.

On top of that, Jorginho showed his innate ability to sniff out danger and get Italy back on the move, with his 48 recoveries the second-highest among outfield players.

Given the presence of these two, it's no wonder Italy strung together the third-most sequences of 10 of more passes (123), yet at no point did you feel they got in each other's way, which again is testament to Mancini's setup.

Turning a weakness into a strength

The fact Italy were successful despite not having a particularly convincing striker highlighted the effectiveness of other areas of the team.

Ciro Immobile was Mancini's pick to lead the line. He wasn't necessarily bad, as his goal involvement output of four (two goals, two assists) was only trumped by Patrik Schick and Cristiano Ronaldo.

However, the Lazio man was by no means deadly in front of goal, hitting the target with just three of 18 shots. Among players with at least 10 attempts, just four were accurate with a smaller percentage than Immobile (16.7 per cent).

But so fluid were Italy that it didn't really matter. Immobile was one of five Italy players to net two goals, something no team has achieved at the Euros since France did in 2000.

At Italy's Coverciano coach training facility, there is said to have been a growing focus on the development of what are essentially formation-less tactics, and the fact Italy carried a threat from so many different positions suggests such a future actually isn't that far away.

Further to this, Italy showed real flexibility in attack. Sure, they scored 10 times inside the box, a figure third only to Spain and England, but the difference is the Azzurri also netted three from outside the area – no team managed more.

While you might expect that to reflect significantly in their expected goals (xG), Italy still pretty much scored exactly the number of goals one would ordinarily expect from the quality of their chances (13 goals, 13.2 xG), albeit one of those was an own goal.

Whether Italy have enough talent coming through to sustain this level and establish the first international 'dynasty' since the Spain side that won Euro 2008, the 2010 World Cup and Euro 2012 is another debate.

But there's little doubt Mancini has the know-how to make them the team to beat if the production line doesn't dry up.